Noel KH Chia, an IACT-approved instructor, is currently a special needs consultant and trainer in private practice. M.L Ng, a qualified educational psychologist, is also the founder of NeuroLAT Training Systems. Both are actively involved in working with people with special needs.

According to the Oxford Dictionaries (2016), cognition is “the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses” (para.1). The word cognition comes from the Latin verb cognosco (i.e., con means ‘with’, and gnōscō means ‘know’) and is itself a cognate of the Greek derivative, gi(g)nόsko, which means ‘I know, perceive’) (Liddell & Scott, 1940), and according to Franchi and Bianchini (2011), it means “to conceptualize or to recognize” (p.xiv).

Cognition encompasses many aspects of cognitive functions as well as processes that include attention and concentration, the concept formation of knowledge, memory, rational thinking (i.e., judgment and evaluation), reasoning and logic, computation, problem solving and choice/decision making, receptive and expressive language processing that includes different levels of comprehension as well as composition of ideas and thoughts. Cognitive processes use existing knowledge and generate new knowledge.

Cognitive Processes

Cognitive processes (aka mental functions or operations) are often used interchangeably to refer to cognitive functions such as attention, comprehension, decision making, judgment, memory, perception, problem-solving, and reasoning which also constitute executive functioning (Rabi, Lau, & Ng, 2019). In short, cognitive processes are those involved in cognition, i.e., acquisition, processing, and application of knowledge and information.

The cognitive process of acquiring knowledge and experience allows us to process the sensory information we receive. These include our abilities to analyze, evaluate, retain information, recall experiences, make comparisons and determine action (Giles, 2005). Although knowledge and experiential acquisition as a composite cognitive process has an innate component, its bulk of cognitive skills are learned or deliberately acquired (e.g., self-taught or being taught by others more knowledgeable and experienced). According to Chia (2010), when this ability to do so fails to occur normally, cognitive weaknesses are the consequential result and diminish a person’s ability to learn or even the will to want to learn (i.e., less motivated and loss of interest). Hence, it becomes necessary for the person to seek some kind of intervention to address the issue of concern.

Cognitive Abilities and Skills

Cognitive abilities and skills are two different things and must not be confused or mistaken one for the other. There is a difference between skills and abilities. In fact, skills are abilities. However, a skill is a composite of abilities, techniques and knowledge (DB.net, 2018; Julita, 2011). They are the ones that make a person do tasks at a higher degree or standard with goaloriented expectations of improvements or positive changes in an individual’s performance.

DB.net (2018) and Julita (2011) have provided a brief summary of skills and abilities as shown below:

- A skill is acquired, but an ability is more of constitutional origin or inherited.

- A skill can be practiced to perfection but not the ability, which a person either possesses or not. For instance, talent is an ability, not a skill.

- A skill is goal-directed and it expects a person to attain a higher performance level. However, the ability does not necessarily equate to exceptional performance.

- A person’s level of functionality depends more on ability than skill.

- An ability is more stable than a skill.

In summary, cognitive abilities are innate but cognitive skills are acquired and can be trained or practiced to attain mastery. That means cognitive skills can be practiced and improved with the right teaching approach or strategy. Using the appropriate therapy (e.g., special needs educational therapy, remedial teaching, and cognitive training), the brain of a struggling learner can actually be “rewired” and cognitive function can be restored or enhanced (Goswami, 1998). Like terra-forming, literally means Earthshaping of an alien or unearthly place, cognitive rewiring has been termed as psycho-forming, i.e., transforming the mind of an atypical individual to resemble the way a neurotypical mind would think, perceive, reason like the majority, especially so that it can function like a typical or normal person who. While weak cognitive skills can be strengthened, normal cognitive skills can be enhanced to increase ease and performance in learning. That is why for children, especially those in Asia, “enrichment programs (e.g., abacus, phonics) offered outside the regular school system still play an important role in educating the whole child” (Chia,2010, p.41).

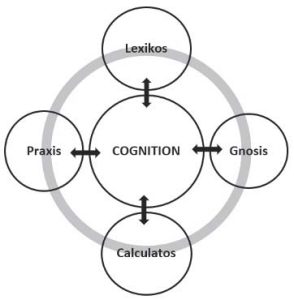

According to Chia (2010), cognition, which he defined as the act of apprehending or ability to grasp or lay hold of mentally, can be categorized into four mental components (see Diagram 1): “(1) lexikos (linguistic ability); (2) calculatus (mathematical ability); (3) praxis (i.e., from ideation through perceptuo-motor planning to execution of the intended act); and (4) gnosis (i.e., knowledge of self in response to somatic needs as well as interaction with the environment at large to establish the knowledge of the world). Any developmental interference to any of these four components

can result in some kind of learning disability such as dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia and/or dysgnosia. On the other hand, if there is any acquired injury to the brain affecting any of these four components, alexia, acalculia, apraxia and/or agnosia can happen, respectively” (p.42-43).

Diagram 1. The 4 Mental Components of Cognition

The Hierarchy of Abilities and Skills

Whether a person can perform well in studies or at work depends on the hierarchy of abilities and skills as proposed by Chia (2012) and not all the abilities and skills are of cognitive nature. There are five main block levels as briefly described below:

Block I-Innate Abilities & Skills: Also known as the Foundation Block, it refers to the core block of an individual’s innate abilities which deal with the use of language to communicate, abstract thoughts and reasoning skills, memory retention as well as problem-solving skills. An example of an assessment tool for this level is an IQ test.

Block II-Sensory Behavioral Abilities & Skills: This second block focuses on the sensory-perceptual-motor coordination and related behavioral skills and abilities involving balance/motion of the body (vestibular) & position of body (proprioception). An example of an assessment tool for this level is the Sensory Profile (Dunn, 1999).

Block III-Adaptive Behavioral Abilities & Skills: This third block concerns the adaptive behavioral abilities and skills necessary for performing daily living activities, social interaction, communication, self-help skills (e.g., toileting, dressing, bathing), personal hygiene, and other related practical skills. An example of an assessment tool for this level is the Adaptive behavior Diagnostic Scale (Pearson, Patton, & Mruzek, 2016).

Block IV-Socio-Emotional Behavioral Abilities & Skills: The fourth block consists of socio-emotional behavioral abilities and skills that cover adaptive, internalizing, and externalizing behavioral skills. This block can also be determined by assessment tools such as Social Responsiveness Scale-2nd Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012).

Block V-Cognitive Behavioral Abilities & Skills: The fifth block focuses more on academic or educational attainments, which include higher levels of cognition, involving word knowledge (i.e., active and passive vocabularies), general knowledge, ability to count and perform operational functions involving numbers, and ability to carry out activities using both verbal and nonverbal reasoning skills. Most of the assessment tools are academic attainment measures such as Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-3rd Edition (WIAT-III; Wechsler, 2009) and Peabody Individual Achievement Test-Revised (PIAT-R; Markwardt, 1989). These five key blocks of abilities and skills provide a framework for cross-battery assessment (X-BA; see Flanagan & McGrew, 1997, for detail) so that an assessment team can review a case and decide on the appropriate tests to be administered, taking into consideration a client’s condition based on feedback from his/her family and significant others.

Broad and Narrow Cognitive Abilities

The cross-battery assessment (X-BA) is the process by which assessors use information from multiple test batteries to help guide in their diagnostic decisions and to gain a fuller picture of an individual’s cognitive, conative, affective, and sensory abilities and skills than can be ascertained through the use of multiple-battery assessments of the same block of abilities and skills or single-battery assessments (Flanagan & McGrew, 1997).

The approach taken in X-BA was first introduced in the late 1990s and offers practitioners the means to make systematic, valid, and up to-date interpretations of intelligence batteries and to augment them with other tests in a way that is consistent with the empirically supported Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory of cognitive abilities (Flanagan, Ortiz, & Alfonso, 2007). With the introduction of X-BA, it has brought to light that there are numerous cognitive abilities that can be represented by broad and narrow cognitive abilities. Today, the CHC model of human cognitive abilities has emerged as the consensus psychometricbased model for understanding the structure of human intelligence (McGrew, 2009). In fact, the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) became the first test reported to measure all of the proposed broad cognitive abilities in the most recent iteration of the CHC model (Schneider & McGrew, 2012).

The CHC theory came about with the development of the Gf-Gc theory (Horn & Cattell, 1966) and Carroll’s (1993) three-stratum model. The term Gf represents the broad ability of fluid reasoning while the other term Gc represents the broad ability of comprehension-knowledge. According to McGill (2017), this theory “conceptualizes cognitive abilities within a hierarchical taxonomy in which elements are stratified according to breadth. The most general ability resides at the apex of the model at Stratum III and is referred to as a general factor of intelligence (g)” (p.265). At the next level or Stratum II, it includes the following 18 broad abilities under four main domains: (1) Intelligence as a process, which includes Gf-Fluid Reasoning, Gwm-Short-Term/ Working Memory, Gl-Learning Efficiency, Gv-Visual Processing, and Ga-Auditory Processing; (2) Intelligence as knowledge, which includes Gc-Comprehension-Knowledge, Gkn-Domain Specific Knowledge, Grw-Reading and Writing, and Gq- Quantitative Knowledge; (3) Intelligence as process (speed/ fluency), which includes Gr-Retrieval Fluency, Gs-Processing Speed, and Gt-Reaction and Decision Speed; and (4) other and tentatively identified domains, which include Gps-Psychomotor Speed, Gp-Psychomotor Abilities, Gei-Emotional Intelligence, Go-Olfactory Abilities, Gk Kinesthetic Abilities, and Gh-Tactile Abilities (Schneider & McGrew, 2018). Currently, there is a lack of well-supported evidence for the narrow abilities of Gk and Gh

“Thank you for a terrific weekend of informative

presentations! I know it takes a lot of time to organize and

provide all the elements for this type of success.”

-Terri Raymond, Sedona, AZ

but research is still ongoing. At the bottom of the model are 91 narrow abilities (Stratum I) which are organized according to their mapping onto the Stratum II dimensions” (p.265).

Within the broad cognitive abilities, there are also major cognitive abilities and minor cognitive abilities. For example, under the Gf-Fluid Reasoning, the major narrow cognitive abilities are Gf-I-Induction and Gf-RQ-Quantitative Reasoning while there is currently only one minor narrow cognitive ability: Gf-RG-General Sequential Reasoning. Two other minor narrow cognitive abilities Gf-RE-Reasoning Speed and Gf-RP-Piagetian Reasoning are designated as tentative abilities, which are considered intermediate stratum abilities (Schneider & McGrew, 2018).

Cognitive Training Programs

Cognitive training is a technique within a treatment program to help improve the ability of someone, say, with brain injury or other neurological condition, to function as normally as possible. The exercises offered in a cognitive training program (CTP) are designed to help achieve targeted therapeutic goals (e.g., enhance self-esteem, reduce frustration, and develop problem-solving strategies). The CTP can be carried out in the schools to ameliorate problems relating to learning challenges. Generally, the goal of a CTP is to improve attention, learning performance, judgment, organizing and planning, perception, reasoning, working memory, and overall executive functioning. Moreover, developing such cognitive abilities can help to enhance selfawareness, self-confidence, and emotional stability. Today, there are many commercialized CTPs (e.g., ACTIVATETM, BrainRx, CogniFit, MyNeuroLAT, and NeuroTracker) available in the market.

Practitioners using cognitive training technique to work with their clients may want to consider the following questions to serve as guidelines when selecting which CTP best suits their client’s needs:

• What is the client’s issue(s) of concern? (Refer to the client’s psychological assessment report.)

• Is CTP an appropriate technique to meet the client’s needs?

• What does the selected CTP offer to deliver in its training objective(s)?

• Is the CTP constantly upgraded in its development?

• What are the broad cognitive abilities covered in the CTP? (Take note of major and minor cognitive abilities as well as those tentative abilities.)

• What are the narrow cognitive abilities covered in the CTP? (Take note of the suitability of the tasks designed for each narrow cognitive ability. Observe the client’s task behavior as s/he performs the activity.)

• Does the client manage to master the skill(s) associated with the specific narrow cognitive ability?

“Thank you for all you do for the members of IACT and

IMDHA.”

-Suzy Day, Medford, OR

References

Carroll, J.B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factoranalytic studies. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Chia, K.H. (2010). Counseling students with special needs. Singapore:Pearson Education/Prentice-Hall.

Constantino, J.N., & Gruber, C.P. (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale Second Edition (SRS-2): Manual. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

DB.net (2018). Difference between ability and skill. Retrieved [online] from: http://www.differencebetween.net/language/difference between ability-and skill/#ixzz5WS3m4ldH.

Dunn, W. (1999). Sensory Profile. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation.

Liddell, H.G., & Scott, R. (1940). In H.S. Jones & K. McKenzie (eds.), A Greek-English lexicon. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Flanagan, D.P., & McGrew, K.S. (1997). A cross-battery approach to assessing and interpreting cognitive abilities: Narrowing the gap between practice and cognitive science. In D.P Flanagan, J.L. Genshaft, & P.L. Harrison (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (pp.314-325). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Flanagan, D.P., Ortiz, S.O., & Alfonso, V.C. (2007). Use of the crossbattery approach in the assessment of diverse individuals. In A.S. Kaufman & N.L. Kaufman (Eds.), Essentials of cross-battery assessment (2nd ed.) (pp.146-205). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Franchi, S., & Bianchini, F. (2011). On the historical dynamics of cognitive science: a view from the periphery. In The search for a theory of cognition: Early mechanisms and new ideas (pp. xi–xxvi). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Rodopi Publishing.

Giles, B. (Ed.) (2005). Thinking and knowing. Kent, UK: Grange Books.

Goswami, U. (1998). Cognition in children. London, UK: Psychology Press.

Horn, J.L., & Cattell, R.B. (1966). Refinement and test of the theory of fluid and crystallized general intelligences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 57(5), 253.

Julita (2011). Difference Between ability and skill. DifferenceBetween.net. Retrieved [online] from: http://www.differencebetween.net/ language/difference-between-ability-and-skill/.

Markwardt, F.C. (1989). Peabody Individual Achievement Test-Revised (PIAT-R). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

McGrew, K.S. (2009). CHC theory and the human cognitive abilities project: Standing on the shoulders of the giants of psychometric intelligence research. Intelligence, 37, 1-10.

Pearson, N.A., Patton, J.R., & Mruzek, D.W. (2016). Adaptive Behavior Diagnostic Scale (ABDS). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Rabi, N.M., Lau, M.J.M., & Ng, M.L. (2019). Improving executive functioning skills in children with autism through cognitive training program. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 8(3), 303-315.

Schneider, W.J., & McGrew, K.S. (2018). The Cattell-Horn-Carroll theory of cognitive abilities. In D.P. Flanagan & E.M. McDonough (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests and issues (4th ed.) (pp.99-145). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Wechsler, D. (2009). Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-3rd Edition (WIAT-III). London, UK: The Psychological Corp.

Woodcock, R.W., McGrew, K.S., & Mather, N. (2001). Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing.